Manuscripts on View

Agnese, Battista (16thcent.), Portolan Atlas, Venice, ca. 1535-1538. LJS 28, parchment, 8 ff, in Latin, Fols 3v-4r.

Medieval sea charts, called portolan charts since the 1890s, are remarkable for both their visual splendor and spatial accuracy. The history of these charts remains mysterious, with some scholars dating their invention to antiquity. Portolan charts were at least used since the second half of the 13th century, which roughly coincides with the development of the mariner’s magnetic compass likely used in their creation. Compositionally, portolan charts have two basic elements: the coastal outlines and the network of rhumb lines, which were probably drafted first. Though some sea charts certainly did travel on ships to aid in navigation, these beautiful and costly atlases could also function on land as objects of wealth and prestige. This 16th century Venetian atlas features multiple colors, shaded landmasses, and a contemporary goatskin binding.

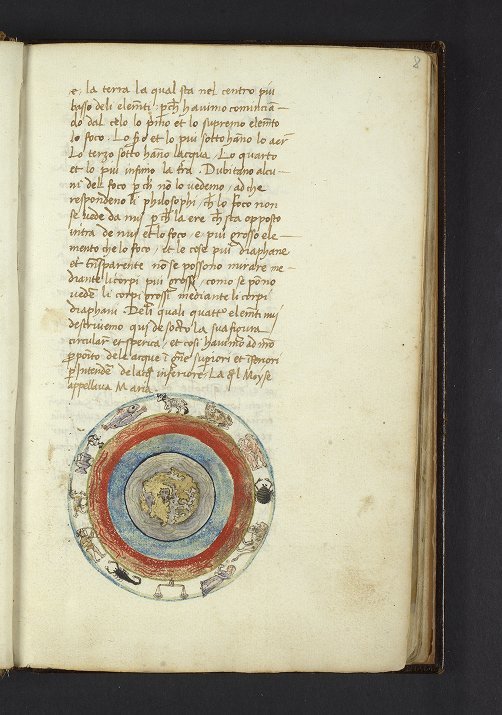

L’arte del navegare, Venice? Italy, 1464-1465. LJS 473, parchment and paper, 84 ff, in Latin, Fol. 7v-8r.

This manuscript contains practical information required for the sailing and navigation so essential for Venetian trade, including passages on shipbuilding, compass construction, cartography, astronomy and meteorology. With fine parchment, wide margins and passages of illumination and gold, the book was designed to be beautiful and would have been extremely costly. It was dedicated to the doge and senate of Venice and is testamentary to the city’s maritime pride. The world map on folio 8r visualizes a blue earth with green continents set within zones of the cosmos and, at the outermost layer, the animals of the zodiac.

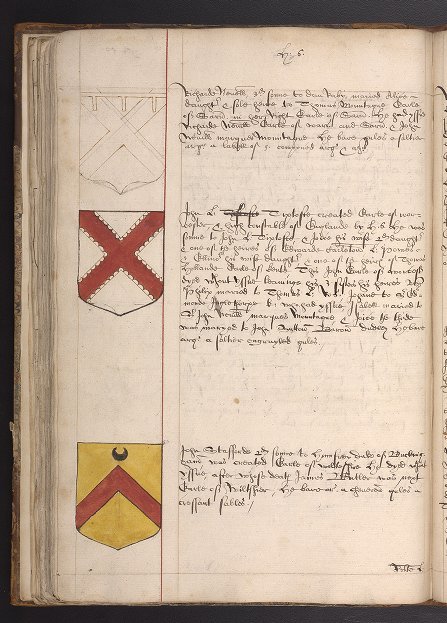

The Names and Armes of All the Nobilitie who were in England at the Tyme of K[ing] W[illia]m the Conqueror, England, 1597.Ms. Codex 1071, paper, 96 ff, in English, Fol. 59v-60r.

This late 16thcentury encyclopedia of English heraldic coats of arms provides a bookend for an essential medieval tradition of identity-making. Including a contemporary index meant to aid in researching specific persons within, the manuscript records the names and coats of arms of monarchs and noble families from Edward the Confessor to Elizabeth I. The five hundred and nine total crests and short biographies represent a complex network of wealth, status and kinship, each family’s coat of arms a paradigmatic form of self-representation. Each monarch receives a section in which are recorded the contemporary title-bearing lords. The manuscript is organized therefore both chronologically and by ties of fealty. The manuscript includes both colored and uncolored pages.

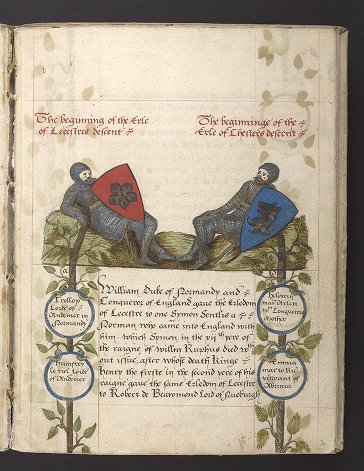

Cooke, Robert (d. 1592), Genelogies of the Erles of Lecestre and Chester, England, ca. 1572, 1573. Ms. Codex 1070, paper, 20 ff, in English, Fol. 1v-2r.

Perhaps commissioned during a major event in the earl’s life, such as his appointment to the Order of the Garter in 1572, this manuscript records the genealogy of Robert Dudley (24 June 1532(?) – 4 September 1588). Although a famous favorite of Queen Elizabeth I with unprecedented power, Dudley and his family had a history of sedition. His role in the brief reign of Lady Jane Grey resulted in Dudley’s imprisonment in the Tower of London, where his graffitied initials remain to this day. A manuscript like this, which traces his noble lineage back to the 11thcentury, provides an auspicious origin story for a figure once embroiled in treason. Noble ancestry could provide a legitimizing framework for his exceptionally high position in the Elizabethan court, as well as his close relationship with the queen.

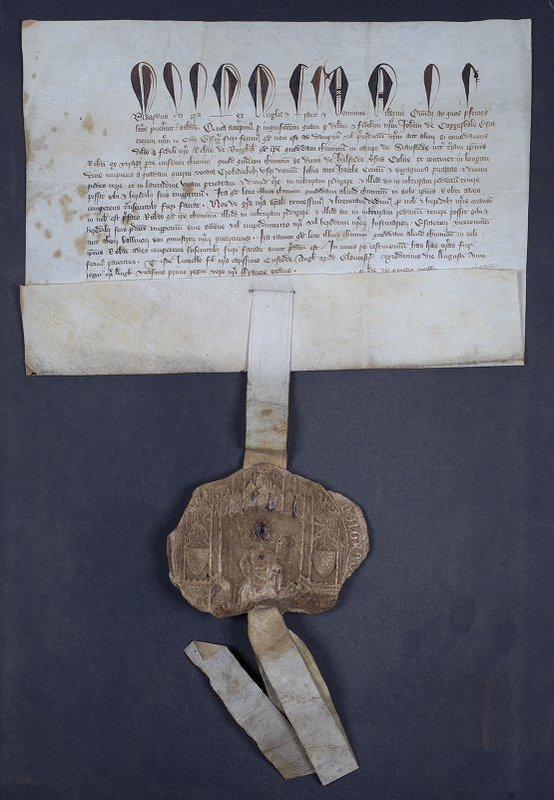

Edward III (1327-1377), Letter patent, England, 1347. LJS 308, parchment and wax, 1 leaf, in Latin.

Seals such as this one in white wax could provide commercial exchanges with royal legitimacy. Witnessed by the son of Edward III and issued by writ of the Privy seal, this document notarized an agreement between a local official and landowner over the relocation of a public road that ran across his land. The seal, though rather worn, asserts the king’s hand and authority in this matter. Receiving such a letter patent, adorned with the large portrait of the king enthroned, would be a potent reminder of the power of the monarch.

Carta Executoria de Hidalguia a Pedimiento, Associated with Charles I (1516-1556), Granada, 1543. LJS 19, parchment, 38 ff, in Latin, Fols. 1v-2r.

Johan Garcia y la Puente of Mora received this letter as endorsement by Charles I of Spain in his litigation to enter the nobility in Granada on 16 June, 1543. Though this example is rather late, carta executoria were prevalent throughout the Middle Ages. Of interest here is the illuminated opening of 1v-2r, a luxurious display of royal might. Here, the coat of arms of Charles I is juxtaposed with a miniature of St. James vanquishing the moors. In this popular miracle story, St. James is resurrected to defeat the moors on horseback. An ultimate Spanish story of Christian virtue defeating the trespassing other, this miniature placed alongside the crest of Charles I aligns the king with Spanish Christian identity as well as military power. Three cameos in the borders of the page also feature St. George slaying the dragon, the Archangel Michael killing the serpent, and a scene of beheading.

Schedel, Hartmann (1440-1514), Liber Chronicarum (Nuremberg Chronicle), Germany, 1493. Inc S-307, paper, 299 ff, in Latin and German, Fols. 99v-100r.

The Liber Chronicarum has been called the last medieval book, and is a cap to the medieval chronicle tradition. Produced in Nuremberg at the end of the 15thcentury, the Nuremberg Chronicle was the most ambitious printing project undertaken since Gutenberg’s bible. Like most printed books, the Nuremberg Chronicle was the product of many hands, a part of the new and vibrant printed book trade of which the city was a center. This costly book had an ambitious print run, easily found even today in many rare book collections. Though encapsulating the known history and geography of the period, the city of Nuremberg is at the very heart of the work, its detailed and accurate city map located on folio 100. The book is, in a sense, a mirror for prestige and position of the city in a major moment of economic expansion, revealing the way its producers imagined the world and their place in it.

Hamd Allāh Mustawfī Qazvīnī (1330-1340), Nuzhat al-qulub, India, ca. 1575-1625? LJS 413, paper, 252 ff, in Persian, Fols. 178v-179r.

Like several of the objects displayed, this manuscript toes the line between history and geography, kinds of knowledge often united in the Middle Ages. The manuscript, in English called “Heart’s Bliss,” also contains information on flora, fauna, geography, history and cosmology, as well as the “wonders of the world.” Though the author of this text was a 14th century Persian historian, this manuscript is a 16th century Indian copy in which a near-contemporary Deccan reader compares his knowledge of his own region in India to the text in an interesting transcultural and trans-temporal conversation.

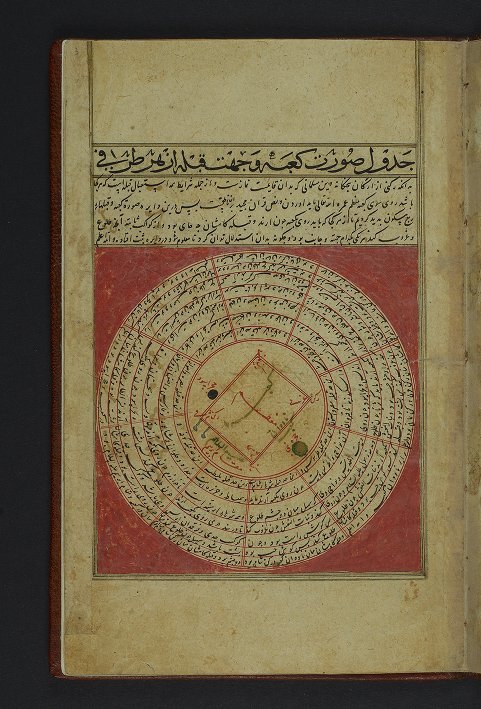

Taqwīm, Iran? ca. 1507. LJS 434, paper, 7 ff, in Arabic, Fols. 2v-3r.

In areas of the medieval Middle East, tables of ikhtiyārāt (elections) were used in an astrological technique for determining auspicious times for carrying out various activities. A half-completed horoscope diagram designed for a location in Northern Afghanistan may provide some clues as to where this manuscript originally called home. The first folio of this manuscript features a colored diagram of the Eastern half of the world with features labeled minutely in Arabic. Folio 3r is a circular index of the distance of various cities from Mecca. Diagrams like this might be useful to medieval Muslims when planning for their pilgrimage to Mecca, or the haaj, one of the five pillars of Islam.

The original souvenir, pilgrim badges were purchased by pilgrims to commemorate their visit to a holy site. As copies of a Divine prototype, pilgrim badges had holy significance, objects of prayer and veneration akin to that bestowed upon the actual shrine. Like seals, pilgrim badges were imprints that could play a role in self-formulation. Pilgrims would paste their collection of badges in the front of their prayer books like relics. This badge features Saint Adrian of Nicomedia, who was venerated at the Abbey of Geraardsbergen in Belgium after his relics were transported there in 1175. According to legend, Adrian was a Roman soldier persecuted for his Christian beliefs by having his limbs smashed with an anvil.

Ibn al-Wardī, Sirāj al-Dīn Abū Hafs ‘Umar (d.1457), Kharīdat al-‘ajā’ib wa farīdat al gharā’ib, Spain, 1419-1450.LJS 495, paper, 268 ff, in Arabic, Fols. 3v-4r.

“The pearl of wonders and the uniqueness of things strange” is the translated title of this cosmographic compendium written in Arabic and attributed to the 14th-century author Zayn al-Dīn ʻUmar ibn al-Muẓaffar ibn al-Wardī. It contains the names of places as well as information on plants, animals, and a brief explanation of the game of chess. Perhaps responding to the interest in flora present in the text, the world map on fols. 3v-4r has a petaled, plant-like quality, to modern eyes more like a diagram of a cell than a map of the world. The places and features illustrated in the colored map are carefully labeled in Arabic, the map stretching across the folios with a wide margin of blank parchment at its borders.

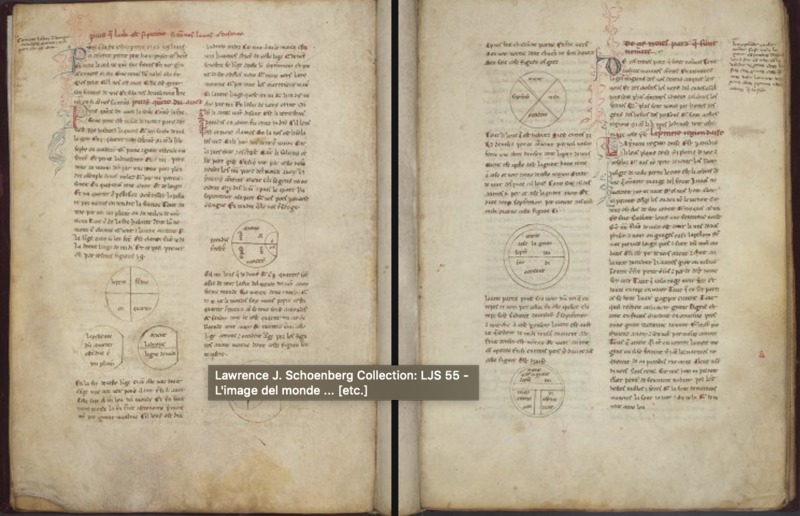

Image du monde, France, ca. 1290. LJS 55, parchment, 52 ff, in French, Fols 9v-10r.

This manuscript is the earliest extant copy of the prose version of Gautier's encyclopedic treatise discussing cosmology, astronomy, meteorology, geography, natural science, and religion. Folio 10r presents several diagrammatic conceptions of the world, including a labeled T-O map. This simplistic formulation of the world is derived from the writings of Isidore of Seville. Literally a T shape circumscribed by a circle, the T-O map subdivided the world into the three known continents, each believed to have been entrusted to one of the sons of Noah. On the verso of this folio is a drawing of a king being blessed by the hand of God.

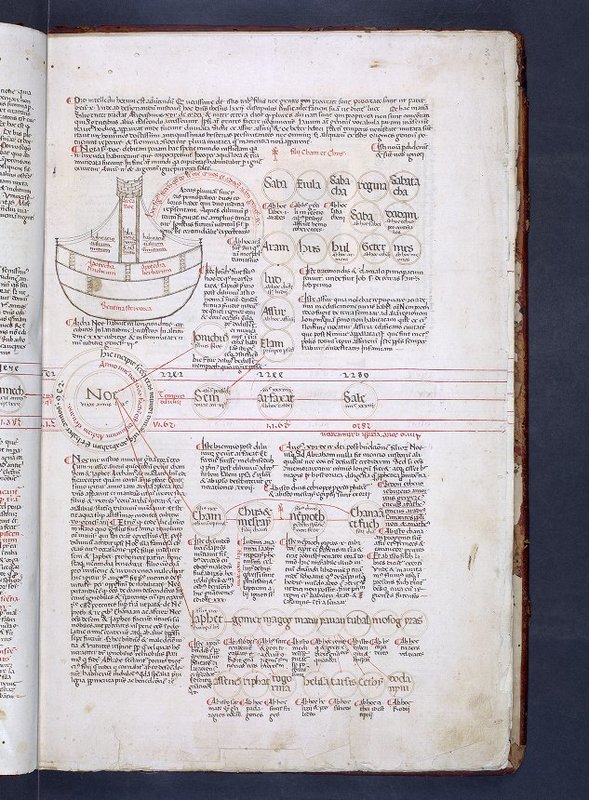

Rolevinck, Werner (1425-1502), Fasciculus temporum, Italy, after 1471. MS Codex 725, paper, 40 ff, in Latin, Fols. 2v-3r.

The diagrammatic layout of this manuscript chronicle relates the history of the world and, more specifically, the Church, from Genesis to the election of Pope Sixtus IV in 1471, revealing the papal preoccupations of its Italian maker. Small, colored architectural illuminations elaborate biblical places such as Noah’s Ark and the Tower of Babel, images that function somewhere between picture and diagram. Rather than simply accompanying a set text, the diagrams and illustrations of this book determine the arrangement and strong horizontal movement of its scroll-like text. Attributed to Werner Rolevinck, the manuscript retains its contemporary, stamped leather binding.

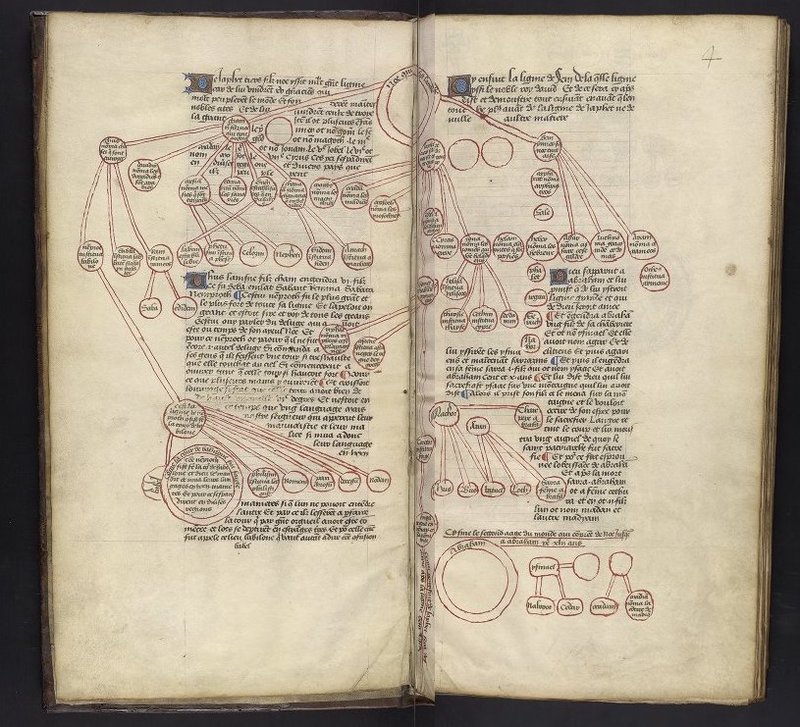

La Generacion de Adam, France, ca. 1425-1450. LJS 266, parchment, 45 ff, in French, Fols. 3v-4r.

This French genealogical chronicle represents an excellent example of medieval formulations of national identity. Containing both mythological and biblical histories, the manuscript includes a number of genealogical diagrams of Adam to Christ, the line of French kings and Holy roman emperors beginning with Charlemagne. It also relates the legendary founding of England and France by the fleeing Trojans after the destruction of Troy. This mélange of medieval history and older myth roots 15thcentury France in a rich past, with origins grounded in heroic and miraculous deeds. It asserts both royal and French identity as inheritors of a long and illustrious history.

Genealogical Chronicle of the Kings of England to Edward IV, England, ca. 1461. Ms. Roll 1066, parchment roll, in Latin.

This roll provides a genealogical history of the world beginning with Adam and ending in King Edward IV of England. Rolls were a common form for genealogical chronicles of this type, their impressive—if slightly unwieldy—form underscoring both the importance of their material and the cyclical nature of time. The format transforms the unrolling of all of human history into a physical act, done in a measured, intrinsically performative way. Like a drama unfolding, the roll begins with Adam and Eve, giving each new generation a revelatory quality. This sort of narrative drama builds and climaxes in the recent line of English kings, attempting to create a neat and awe-inspiring genealogy. For monarchs whose often-fragile power rested upon their legitimacy, this kind of myth-making obscures moments of genealogical uncertainty or political unrest to formulate an ultimate, God-bestowed authority.