Part I: Medieval Theories of Music

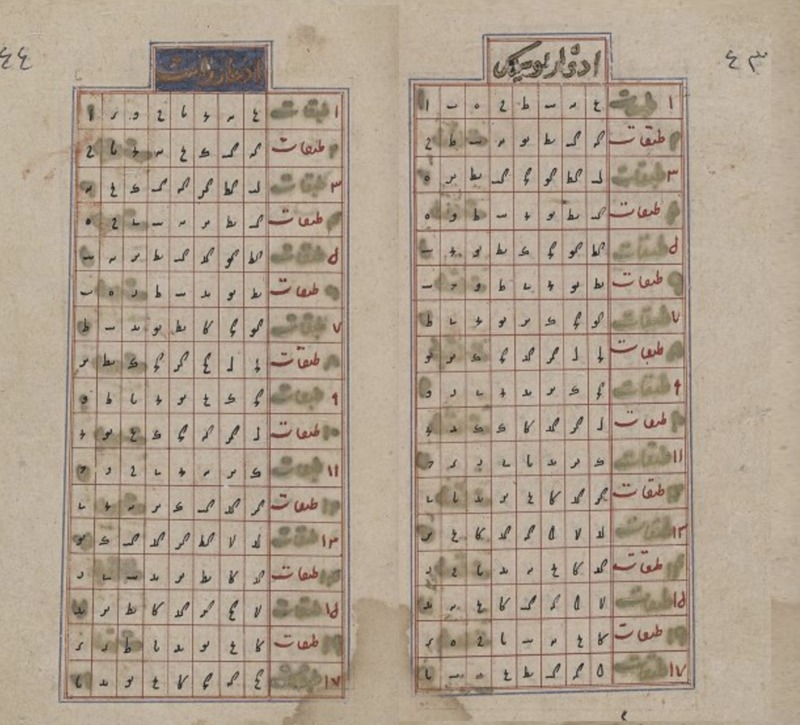

This manuscript contains Safi al-Din al-Urmawi’s Kitab a-Adwar, or Book of Cycles, the most highly transmitted treatise on music theory in the Islamic world. It was written for Musta’sim, the last of the Abbasid caliphs. The treatise includes the division of frets, the ratio of intervals, consonance and dissonance, cycles, rhythmic and melodic modes, and a commentary on the 5-string oud, an innovation to the instrument at the time. By the eighteenth century, Urmawi’s description of the octave began to influence European scholarship on music theory.

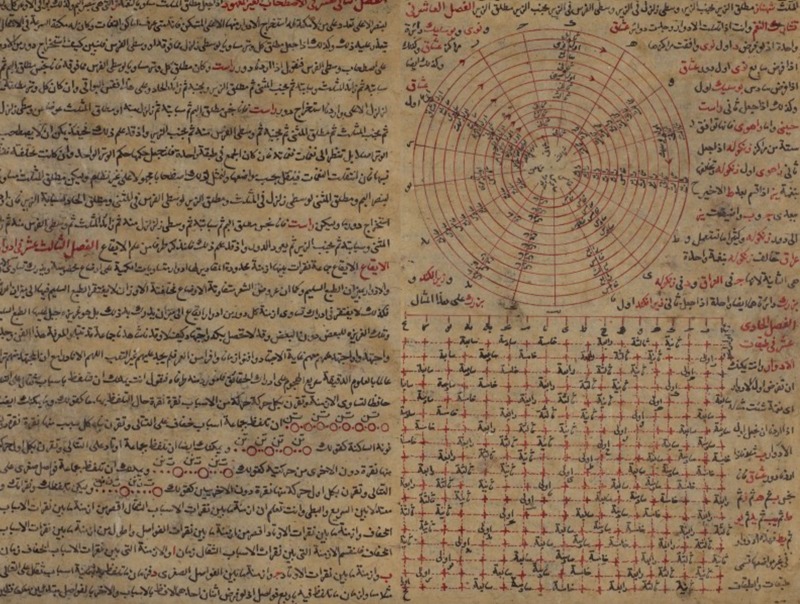

Urmawi’s second treatise on music theory, The Sharafian Treatise On Musical Proportions, is divided into 5 discourses comprised of subjects such as acoustics and sound, intervals, the Arabic transcription of the 15 Greek names for notes, rhythm, and performance. Urmawi composed his second treatise after the fall of the Abbasid caliphate for his new patron, the son of the Mongolian vizir, Shams al-Din al-Juwayni. The diagrams represented in fols. 21v-22r feature Urmawi’s pioneering work on the divisions in the fourth and fifth octaves.

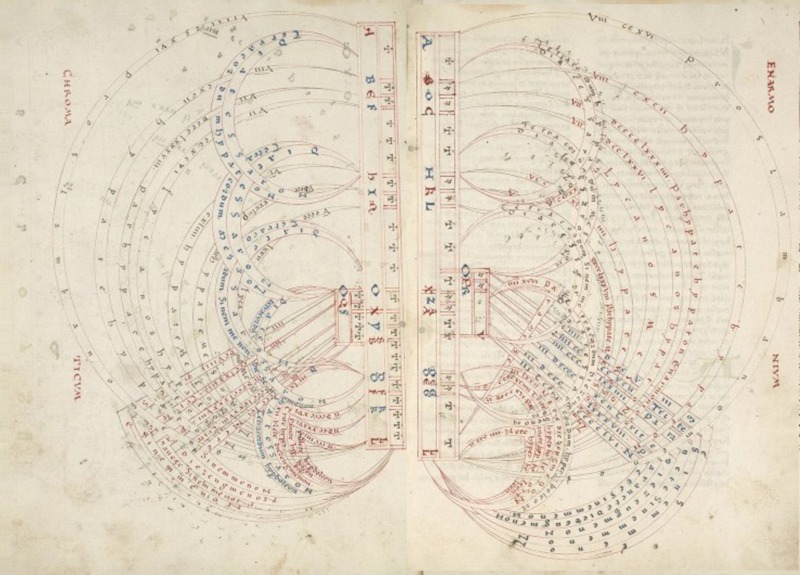

Boethius’s sixth century Latin treatise on the theory of ancient music became the foundational textbook for the study of music across the medieval world, influencing scholars from Baghdad to Beauvais. This fifteenth century copy of De Institutione Musica is remarkable for its combination of the work’s original Pythagorean based principals along with many updated diagrams related to ratio and pitch. These illustrations demonstrate later developments of theoretical principles in music and have been elaborately and carefully reproduced in this particular manuscript. Pictured in folios 41v-42r are ornately drawn schematics of the chromatic and harmonic scales.

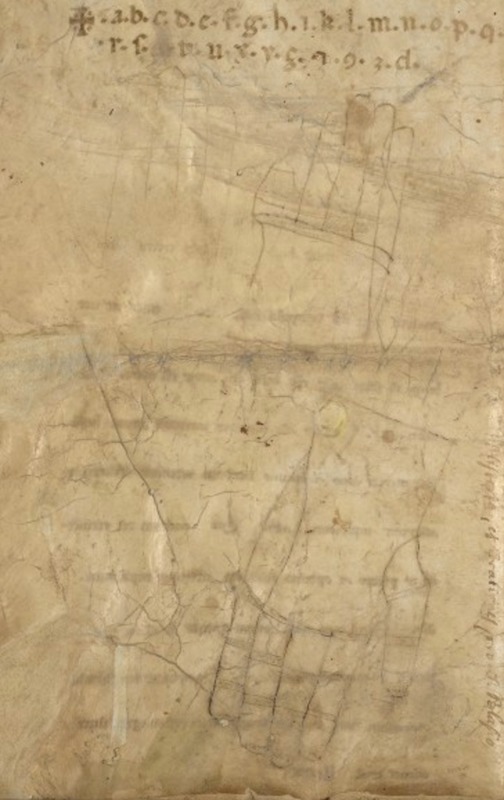

In addition to an account of the martyrdom of Saint Blaise, who is illustrated on the first folio, this 13th century Italian manuscript also includes readings and chants for the Mass in his name. The other texts found at the end of the manuscript, written in different hands, were designated for baptisms. It also contains one group of prayers for vestments and two rough representations of Guidonian hands on the final folio (fol. 8v). The Guidonian hand was a mnemonic device to help singers learning to sight-sing and to understand the hexachord system.

This miniature monastic manuscript of music and prayers was destined for pedagogical purposes. It begins with the seven-tone scale followed by the standard chants, such as Kyrie, Gloria and Ite missa est, all copied in the different tones. The musical notation of various chants from the liturgical and sanctoral cycles is followed by prayers to Saint Michael, Saint Helena, and Saint Katherine of Alexandria, as well as a number of prayers for the death and burial of different people in medieval society, such as priests, parents, and members of the order. The final recto features an ornate diagram of a Guidonian hand, the teaching tool developed by Guido of Arezzo for the use of learning solfège (fol. 122r). The verso of the final folio contains a ladder diagram of the gamut and John 1.1-12 written inside a decorative blue frame beneath it (fol. 122v).