Part III: Secular Melodies

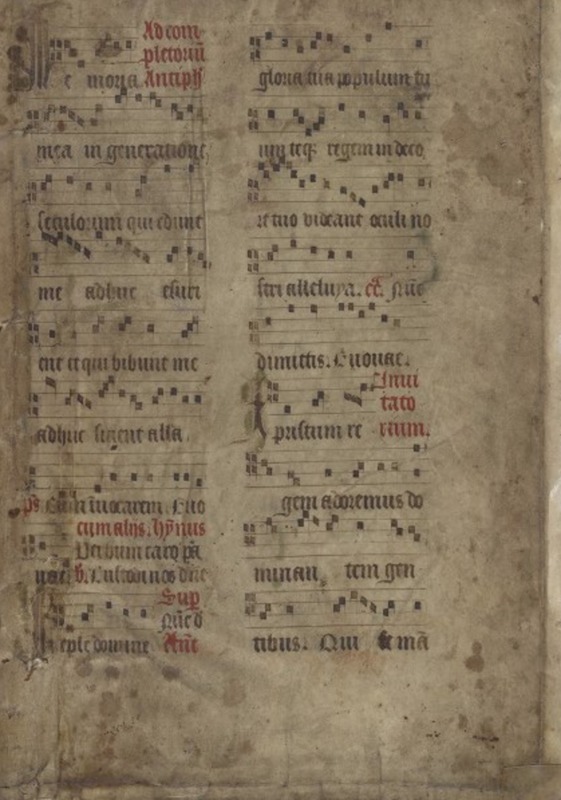

These leaves contain a fifteenth century copy of a thirteenth century biography of St. Catherine of Alexandria. She is said to have lived during the reign of the emperor Maxentius and was renowned for her capacious intellect. This version of the Life of Saint Catherine is attributed to Albertano da Brescia, a thirteenth century Italian legal mind and author who influenced Geoffrey Chaucer. The hagiographic text is bound in vellum from a fourteenth century missal that features text and music beginning with Ecclesiasticus 24:28, “My memory is unto everlasting generations.”

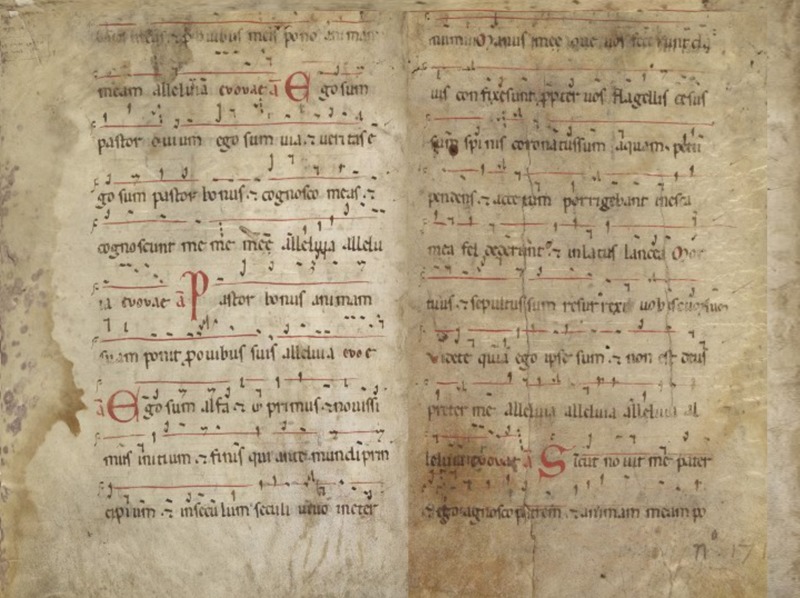

This fifteenth-century Italian collection of legal treatises features articles on civil law, Roman law, and canon law by authors such as Angelo degli Ubaldi, Giovanni d'Andrea, Martino da Fano, and Bartolo of Sassoferrato, whose Tractatus de Guelfis et Ghibellinis (fols. 224v-226v) contains numerous diagrams. While the central text is composed of legal treatises, the book itself contained two bifolia made of parchment which were used as pastedowns and originally came from a twelfth century Italian antiphonal. The bifolia contain chants for Easter with text in protogothic script and with notation in Beneventan neumes on 3-line staves.

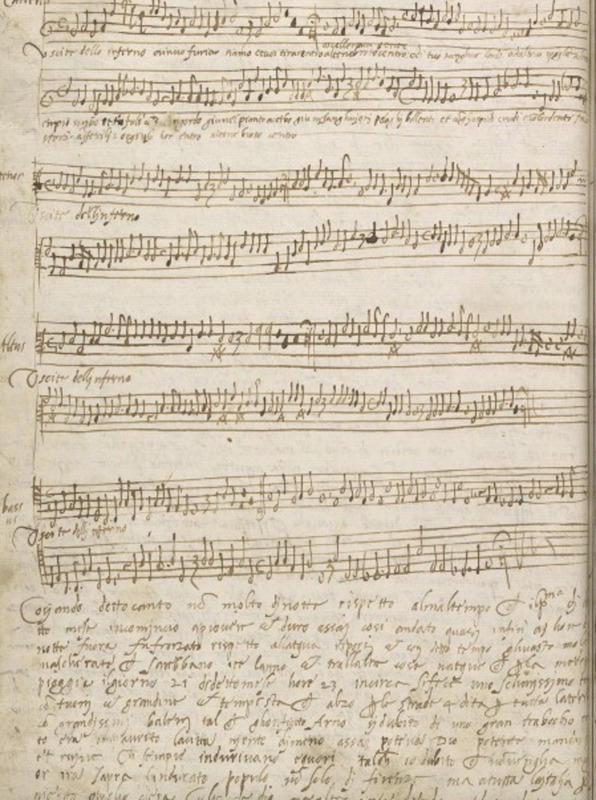

This chronicle of Florentine life begins with the assassination of Alessandro de' Medici in 1537 and continues until 1555. It is replete with descriptions of civic festivals and celebrations, texts and a poem in Italian (fol. 81r). It also features some of the political gossip of the day, as well as little known details of Alessandro's assassination. The manuscript also contains one musical score (fol. 48v). The chronicler details the song’s performance on the night of Carnivale, February 16, 1550; he describes in detail how one of the floats in the carnival procession featured the jaws of Hell and a large devil with flames spewing from his mouth. A group of singers, accompanied by ducal troops dressed in red, sang the song Uscite dello inferno, anime furiose. This song was written in the tradition of the Florentine canti carnascialeschi, which were performed at festivals during the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries.

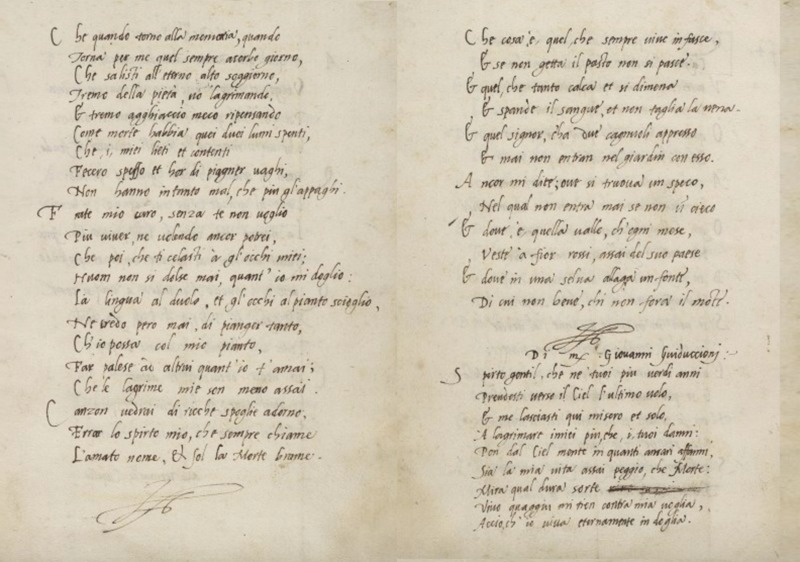

This sixteenth century chrestomathy contains some of the greatest Italian poetry of the fifteenth century; it is comprised of nine sonnets, one canzone, and "motti," or mottos, by the great humanist scholar, Pietro Bembo. It also features poems by Guidiccioni, Capello, Molza, Daniello, Martegli, Tolomei, Della Casa, as well as several anonymous poems written by a single hand in humanistic script. This manuscript was most likely used for pedagogical purposes in the teaching of Italian verse.

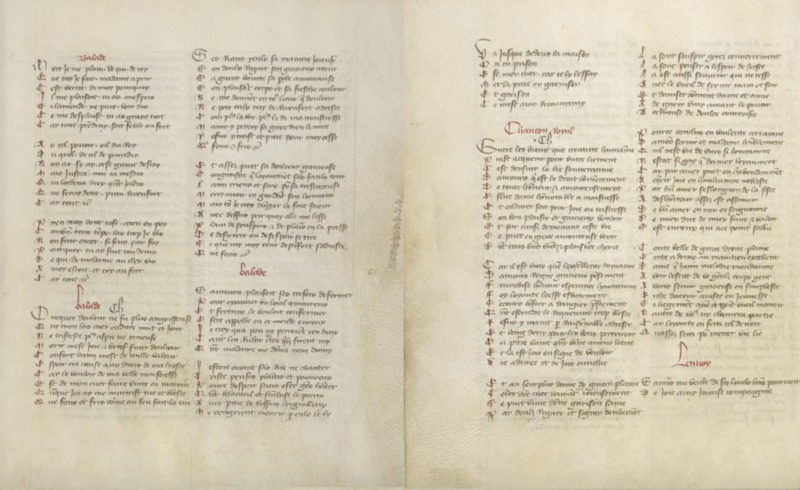

Three scribes copied this collection of 310 forme fixe lyric poems in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. Its title rubricated in French is "Ci sensuient plusieurs bonnes pastourelles, complaintes, lays, et balades et autres choses." It includes one poem by Philippe de Vitry, one poem by Eustache Deschamps, one poem by Brisebare, around twenty-five poems by Oton de Granson, and over one hundred poems by Guillaume de Machaut, as well as anonymous pieces unique to this manuscript. The final poem is a fragment in Italian from Petrach’s sonnet CXLVI of his Rime on fol. 93r. Fifteen of the poems bear the initials "Ch" in a formal hand between the rubricated titles and the text. Some scholars have proposed that the initials might stand for Charles d'Orléans, while others associate them with Chaucer. However, Liza Strakhov has recently suggested that the manuscript was compiled based on the chronology of the poems it contains, since the names of the authors do not appear in the rubrics. Instead, the rubrics list the type of forme fixe in which the poems are written. Therefore, as opposed to grouping the chansons by author, they demonstrate the evolution of the lyric form in French from a song to be sung to a poem to be read, with the enigmatic “Ch” representing change.