Almanacs and Astrology

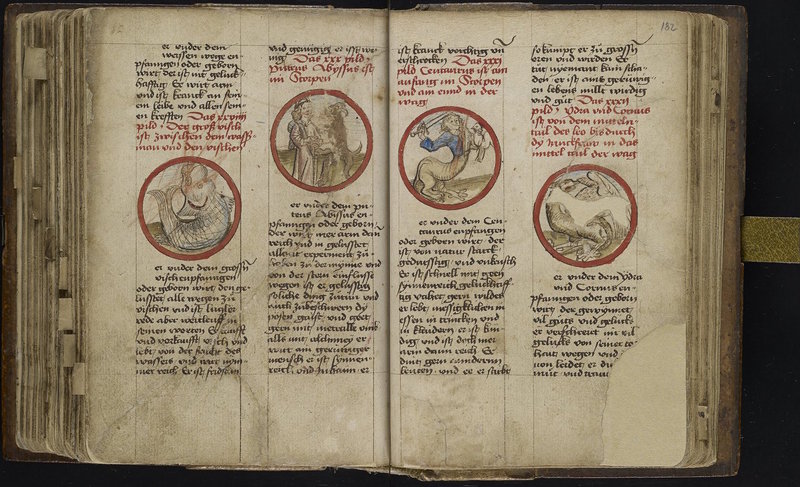

Johannes Lichtenberger (1440-1504), Prognosticatio; and other texts. Germany (Nuremberg?), late 15th century. LJS 445, paper, in Middle High German. Fols. 181v-182r.

This anthology exemplifies the fluid boundaries between manuscript and print traditions in the late fifteenth century. It contains material from three incunables: Johannes Lichtenberger’s Prognosticatio (Heidelberg, 1488; a book of astrological predictions about the Church and the Holy Roman Empire) and two editions of Regiomontanus’s calendar (Nuremberg, 1474; Venice, 1478).

These pages are part of a treatise on the constellations based on descriptions by Michael Scotus (1174-c. 1232), court astrologer to Frederick II. A prominent mathematician, philosopher, and translator, Scotus developed a much-copied list of constellations in his Liber introductorius, including two (Tarabellum and Vexillum, or the Drill and Standard) that he invented. The miniatures on display show Piscis Austrinus, Ara/Puteus (the Altar), Centaurus, and Corvus perched on Hydra; Corvus has been damaged by a reader cutting out Canis Minor on the verso.

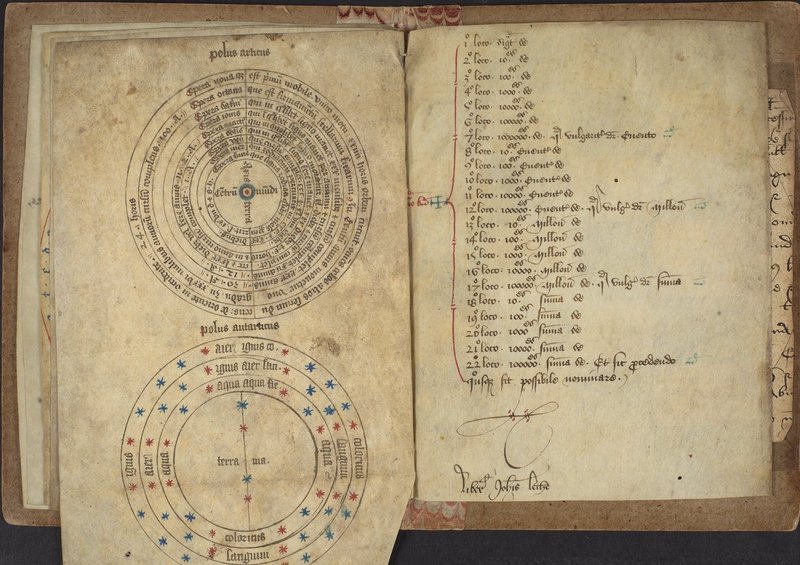

Certain Astrological and Astronomical Figures, Cut Out of a Manuscript Book, Dated 1410. England and Spain, c. 1410. LJS 226, parchment, in Latin. Fols. 6v-7r.

Assembled c. 1861 (fol. 1r), this compilation of three premodern manuscripts testifies to both the diverse practical applications of medieval astronomy and the nineteenth-century trend of collecting medieval illustrations. The first three leaves are drawn from an early fifteenth-century English manuscript, and include a blank horoscope template, a zodiac calendar, and two Kabbalistic diagrams. This text also contains a Latin inscription (fol. 3r) that sheds light on its own production, including the price for a manuscript of twenty-five gatherings (“bought from Master Richard Chamberlain for 16 shillings and 8 pence”). The pages on display show a diagram of the celestial spheres, a more detailed drawing of the elemental spheres, and a leaf from a Spanish manuscript demonstrating how to write astronomically large numbers in Arabic numerals. A drawing of a labyrinth, with an English real estate transaction on the reverse, is inserted at the back.

Taqwīm. Eastern Persia (Timurid Empire), c. 1507. LJS 434, paper, in Persian. Fols. 4v-5r.

Included in this fragmentary taqwīm, or almanac, are half of a world map; a diagram of the Earth’s climatic zones; and half of a horoscope diagram for a location in present-day Afghanistan (26°21’ N, 92°30’ E), dated Friday, 27 Shawwāl 912 (12 March 1507). The illustrations on display represent ikhtiyārāt (elections) for the moon in one of the zodiacal signs. Electional astrology was used to determine auspicious times for performing certain actions, and was a more common pursuit among Islamic and Indian astronomers than among their Christian counterparts. Yet while this manuscript exemplifies the differing emphases of astronomical science across the medieval world, it also reveals the theoretical principles that were shared among cultures, including the belief that celestial bodies exerted influences on the world below.

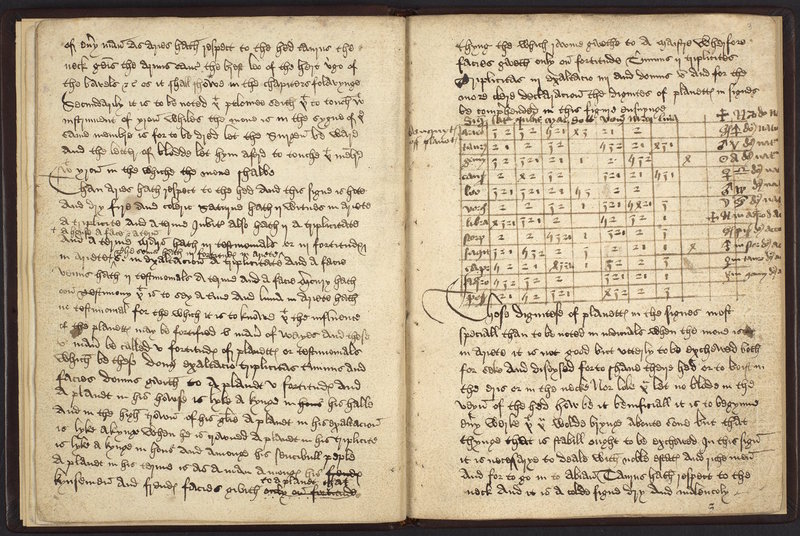

Treatise on Astronomy and Astrology. England, c. 1496. LJS 191, paper, in English. Fols. 2v-3r.

This slim codex approaches astronomy from both theoretical and practical angles. The main text includes nine chapters on such varied topics as ephemerides (the positions of celestial bodies at given times), signs of the zodiac, planets and planetary aspects, the fixed stars, and meteorology. The pages on display, from the third chapter on the “dispositions of the xii signs,” include a table of essential dignities, or the relative strengths of the planets’ positions (first row, beginning with Saturn) in relation to signs of the zodiac (first column). The manuscript ends with three short texts on auspicious times for bloodletting and other medical treatments as well as planting (fols. 15r-18v). The chapter on stars identifies the date of composition as 1496 (fol. 8v), and a later inscription on the end flyleaf describes weather conditions from the vernal equinox to the summer solstice.

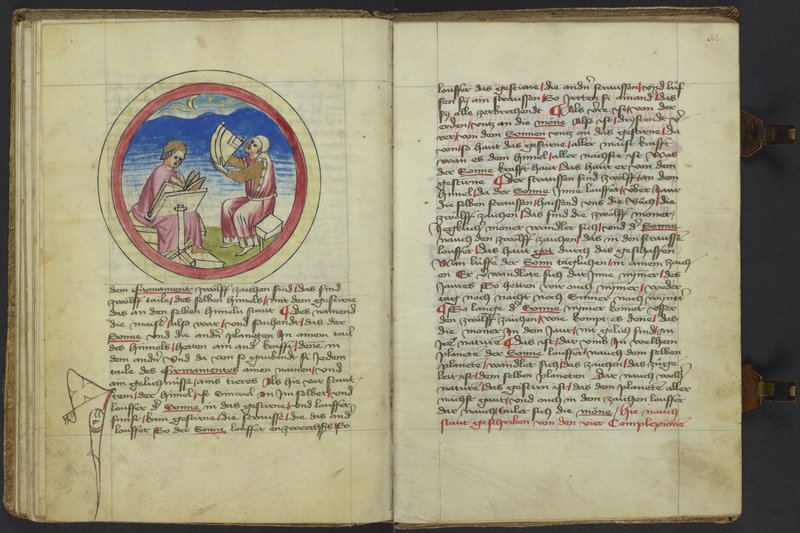

Heinrich Stegmüller, Medical and Astrological Miscellany. Buchau, 1443. LJS 463, parchment, in German. Fols. 41v-42r.

This codex contains a Latin calendar for the diocese of Constance in southern Germany; a text on the zodiac; a treatise on the planets and their “children” (the zodiac signs that they rule); medical texts on the four temperaments, bloodletting, bathing, and powders; and finally, notes in a different hand on the genealogy of the Gundelfingen family. Most of the manuscript is illustrated with vivid pen and ink drawings, including the appropriate zodiac sign and labor for each month of the calendar, a depiction of bloodletting (fol. 52r), and a zodiac man (fol. 54v). The pages on display are part of a short treatise on the skies, with an image showing two astronomers comparing their astrolabe readings to the information in a sturdy tome; the treatise on the humors begins on the next page. The diversity of texts in this volume speaks to the holistic medieval view of the universe, in which one’s work, body, and soul are all affected by the movement of celestial bodies.