Treatises on the Astrolabe

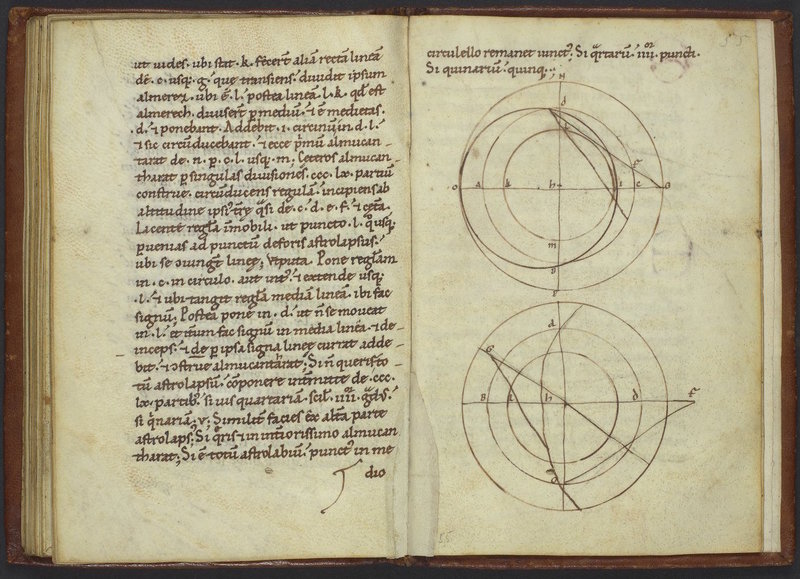

Pope Sylvester II (aka Gerbert of Aurillac, c. 945-1003), De Geometria and other texts (some attributed). Bavaria, c. 1125-1175. LJS 194, parchment, in Latin. Fols. 54v-55r.

This collection of mathematical texts was copied by two twelfth-century scribes and annotated by readers in the twelfth and fifteenth (or possibly early sixteenth) centuries. It includes sections from Gerbert’s Isagoge geometriae, his letter to Adelbold of Utrecht (c. 970-1026) on the area of equilateral triangles with Adelbold’s response, and a short text of less certain authorship on the construction of the planispheric astrolabe, on display here.

The work on the astrolabe exemplifies both the early history of this device in Western Europe and the complementary nature of the seven liberal arts, being placed among texts on geometry. Gerbert was a prominent mathematician before becoming the first French Pope in 999, having studied the trivium at the monastery of St. Gerald in Aurillac and the quadrivium in Spain. Regardless of whether he wrote this particular treatise, he is known to have lectured on the use of the astrolabe and is likely the first person to have brought this knowledge into Christian Europe. In these regards he resembles later figures such as Geoffrey Chaucer, who also traveled extensively and cultivated an interest in astronomical methods.

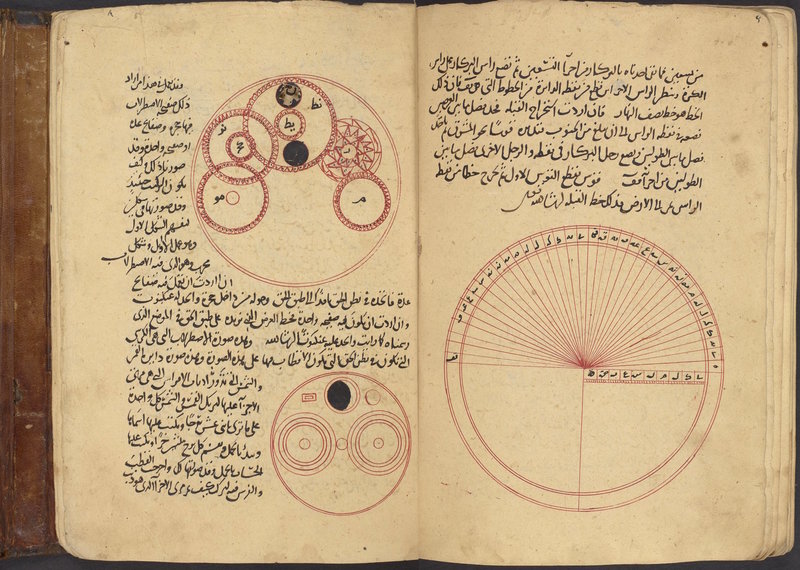

Abū Rayḥān Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al-Bīrūnī (973–1048), Kitāb fī istīʻāb al-wujūh al-mumkina fī ṣanʻat al-asṭurlāb; and other texts. Persia or Anatolia, A.H. 625 (1228). LJS 478, paper, in Arabic. Fols. 72v-73r.

This manuscript begins with a treatise by the renowned mathematician al-Bīrūnī addressing variants of the astrolabe that include updates to its standard discs (which represent projections of the northern sky). He discusses the “crab” and “drum” astrolabes invented by Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh Nasṭūlus, maker of the oldest surviving astrolabe (dated A.H. 315 or 927/928 AD). He also describes Nasṭūlus’s “huqq al-qamar” (“box for the moon”), a mechanism that could be added to an astrolabe to represent phases of the moon. Two treatises on “crab” and “drum” astrolabes follow al-Bīrūnī’s texts; these works were unknown before this manuscript was described and are now attributed to Nasṭūlus. Other texts in this compilation address an instrument for finding the qibla (direction of Mecca) and the compass.

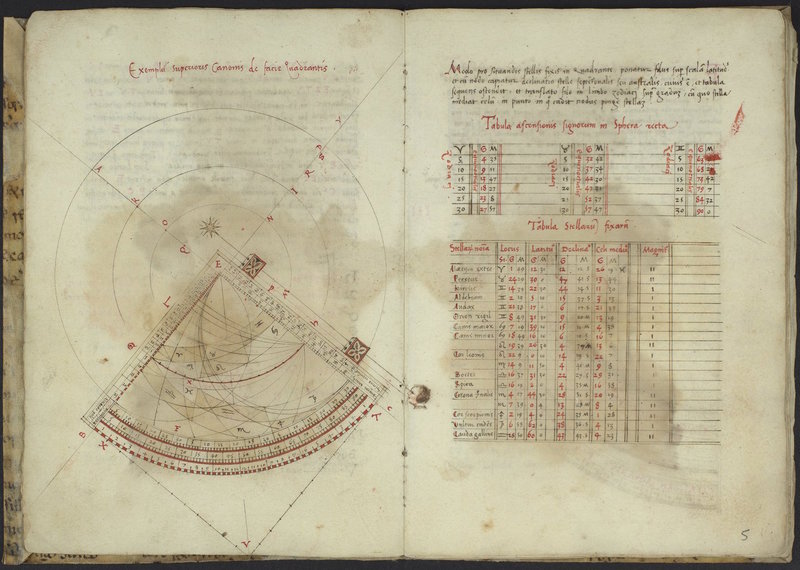

Canones vel op[er]ationes in op[er]ando quadrante. Italy, c. 1502. LJS 497, paper, in Latin. Fols. 4v-5r.

This elegant codex on the functions of the astrolabe quadrant includes computational methods for determining altitude, latitude, the positions of stars, and the twelve houses of the horoscope. It is open to a diagram depicting the quadrant’s use in locating a star, including an appropriately positioned astronomer in the margin, and two tables indicating the ascensions of the zodiac signs and the attributes of the fixed stars.

Other illustrations and tables in this manuscript include the back of the quadrant (fol. 5v), two diagrams showing how to measure the height of a tower (fols. 21v, 23v), a square diagram showing the computation of the astrological houses for Nov. 14, 1501 (fol. 16v), and tables providing the hours of day and night (fol. 10r) as well as sunrise and sunset (fols. 15r-15v) at 45°N. Written in Southern Italy, it is bound in a reused leaf from a twelfth-century copy of Augustine’s In Iohannis evangelium tractatus, written in the Bari form of Beneventan script.