Ptolemy and Cosmology

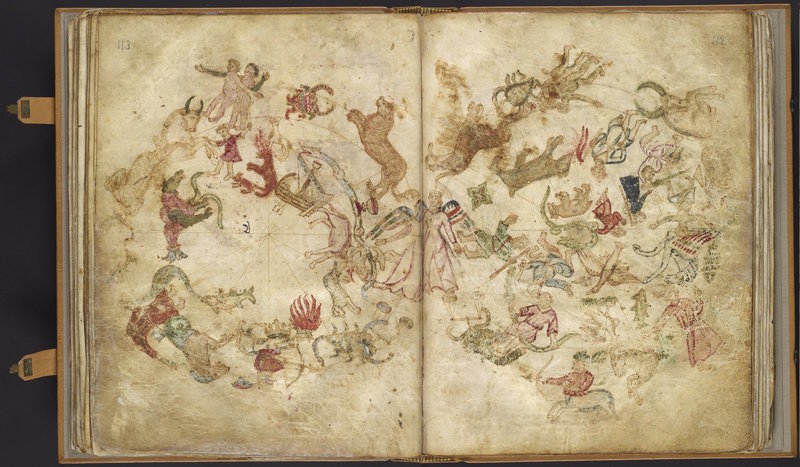

Astronomical Anthology. Catalonia, c. 1361. LJS 57, parchment, in Hebrew. Fols. 56v-57r.

Attesting to the central role of Jewish astronomers in medieval Spain, this volume begins with a treatise on the calendar compiled in 1361 by Jacob ben David ben Yom Tov for Pedro IV of Aragon. It also contains four astrological treatises by the twelfth-century philosopher Abraham Ibn Ezra, including discussions of Indian, Persian, and Babylonian astronomy, and a Hebrew translation of Ptolemy’s Almagest with this remarkable constellation map in ink and gouache. Later folios bear illuminated polychrome constellation images and intricately ornamented tables.

Fewer than thirty-five astronomical maps are known to survive from the Middle Ages, and this example, which shows the northern and southern celestial hemispheres and may have been copied from a globe, offers an especially rare glimpse into medieval Jewish celestial cartography. As Elly Dekker has observed (Illustrating the Phaenomena 458-61), the depictions of certain constellations (e.g. Aquila upside down and standing on Sagitta) and the presence of the Coma Berenices asterism above Leo resemble Islamic maps, while the human figures are drawn in Western European styles.

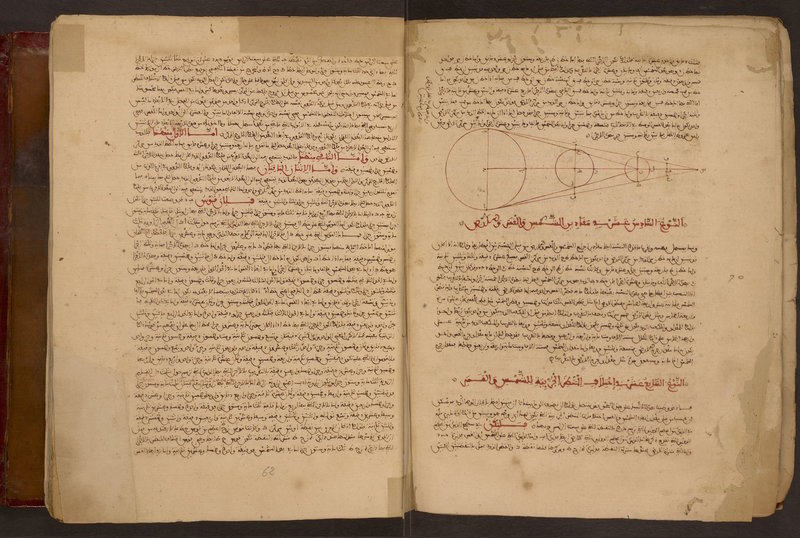

Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100-168 CE), Almagest. Andalusia, 1381. LJS 268, paper, in Arabic. Fols. 61v-62r.

With its rare Arabic copy of the Almagest, this manuscript is a clear example of the intercultural transmission of Ptolemy’s text. A colophon (fol. 185r) identifies the copyist as the Muslim astronomer Aḥmad ibn Aḥmad ibn Salāmah Sanhaja, who produced this manuscript for his Jewish teacher, Qursunna al-Isrāʼīlī, astronomer to Pedro IV of Aragon. It is dated according to Muslim, Jewish, and Christian calendars (783, 5141, and 1381).

Originally called Μαθηματικὴ Σύνταξις (Mathematical Syntaxis), the Almagest summarizes ancient astronomy in thirteen books, including planetary orbits, eclipses, and retrograde motion. The Almagest was translated into Arabic in the ninth century; indeed, its English name derives from the Arabic “al-majisṭī.” The most influential Latin translation was produced by Gerard of Cremona in 1175, while he was employed at the Toledo School of Translators.

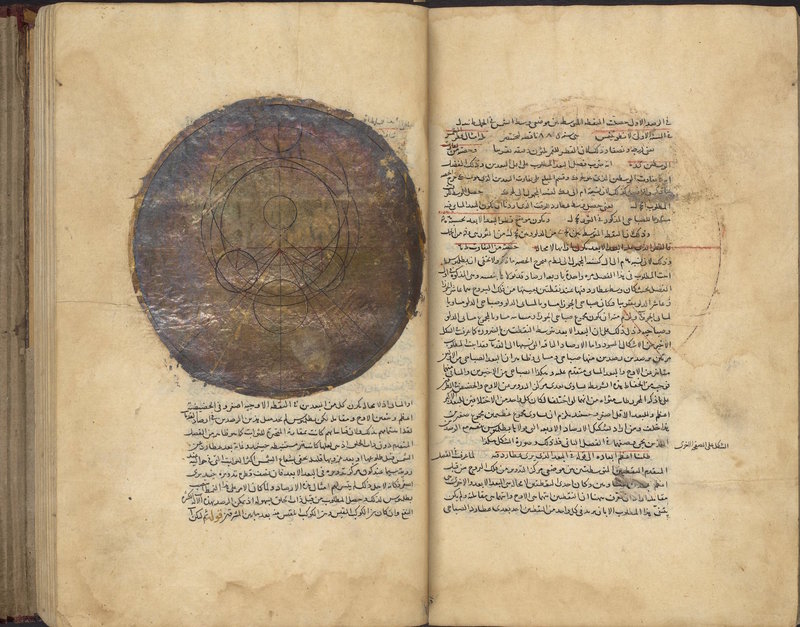

Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Tūsī (aka Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī, 1201-1274), Tahrir al-Majisti, with commentary of Niẓām al-Dīn al-Nīsābūrī (d. 1328/9). Iran (?), AH 13 Dhu’l Qa‘da 813 (9 March 1411). LJS 392, paper, in Arabic. Fols. 156r-157v.

Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī was a prolific philosopher, mathematician, and theologian who is often considered to have created the discipline of trigonometry. His 150 compositions and translations include a work on the astrolabe, an Arabic version of Euclid’s Elements, and the Tadhkira fi ‘ilm al-ha’a (Memorandum of Astronomy), in which he corrected inconsistencies in the Ptolemaic system. In this thirteenth-century recension of the Almagest, he updates several of Ptolemy’s methods, substituting trigonometric equations for Ptolemy’s chord calculations and simplifying the calculation of each planet’s equant (the point around which its epicycle revolves). Also included in this codex is the 1304-5 commentary on this text by Iranian astronomer Niẓām al-Dīn al-Nīsābūrī. Many of the diagrams in this manuscript are illuminated, with gold leaf often extending beyond the precise outlines of the under-drawings (e.g. fols. 4v, 37r, 168r).

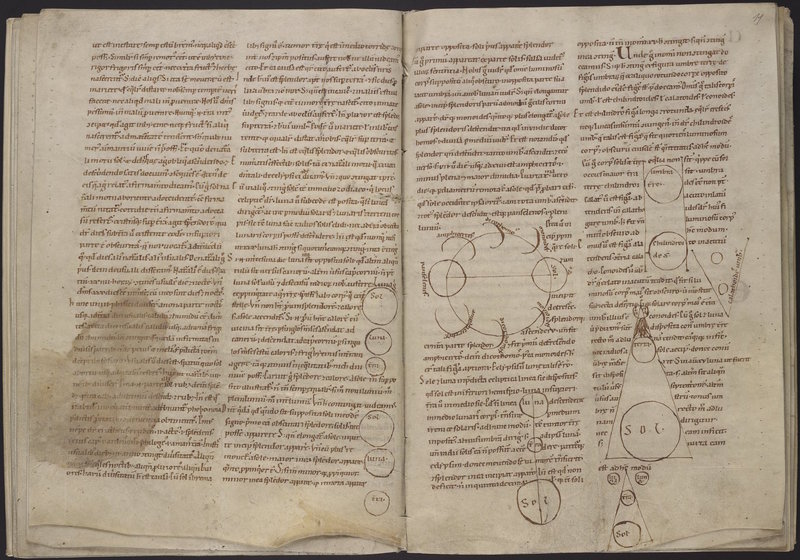

William of Conches (c. 1080-1154), De philosophia mundi (attributed); Hugh of Saint-Victor (c. 1096-1141), Expositio Hugonis de Evangeliis. Germany, c. 1150. LJS 384, parchment, in Latin. Fols. 10v-11r.

William of Conches was a philosopher, teacher (tutor to Henry II of England), and member of the Cathedral School of Chartres, one of the leading educational institutions in eleventh- and twelfth-century Europe. In this four-book summa of philosophical knowledge, he moves down through the celestial spheres, from God and Creation to astronomy, geography, meteorology, and finally human medicine. The Kislak Center’s copy includes sixteen diagrams, including the sketchy drawings of eclipses on display, while much of the section on human procreation has been cancelled by a later reader (fols. 15v-16r). This codex concludes with an otherwise unknown text on the Gospels attributed to the Saxon theologian Hugh of Saint-Victor, which may be the fourth volume of his Liber sermonum.