Later Scholastic Texts

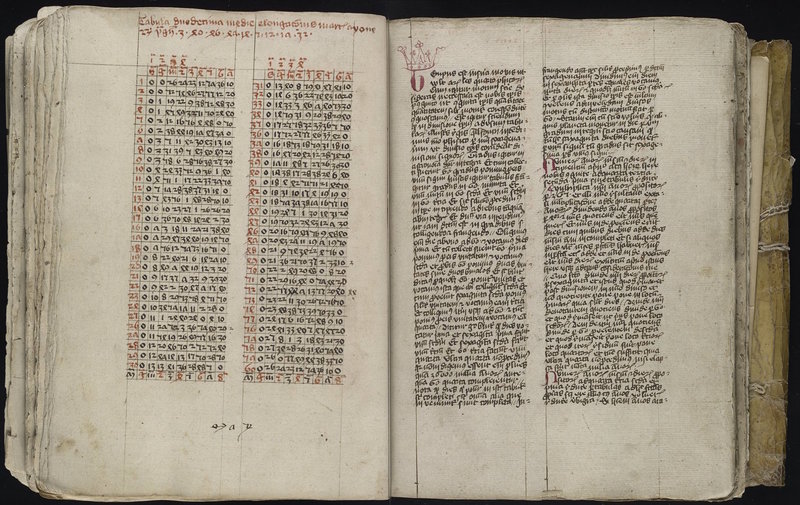

Alfonsine Tables. Prague, 1401-4. LJS 174, paper, in Latin. Fols. 68v-69r.

Created from 1262 to 1272 by the Toledo School of Translators, a scholarly organization established by King Alfonso X of León and Castile (1221-1284) to translate scientific texts from Arabic to Castilian, the Alfonsine Tables contained data required to calculate the position of the planets, sun, and moon in relation to the fixed stars. A team led by Jehuda ben Moses Cohen and Isaac ben Sid produced this updated version of the Toledan Tables (completed by Arabic scholars c. 1080), which circulated widely in Europe after being translated into Latin in Paris during the 1320’s.

This manuscript contains the complete Alfonsine Tables (including average planetary motions, solar and lunar conjunctions, geographic coordinates of cities, and eclipses) and supplementary texts by the fourteenth-century astronomers John of Saxony, Jean de Lignières, and Henricus Selder. It also contains emendations made to the tables for use in Prague, and a short passage on weather prediction by the Baghdad-born Jewish astronomer Māshāʼallāh (משאללה; c. 730-c. 815). Bound in contemporary limp vellum with string ties, this manuscript shows signs of frequent use, with five leaves that have been completely or partially removed (two after fol. 12; fol. 84; two at end), as well as two pages of notes laid in after fol. 1.

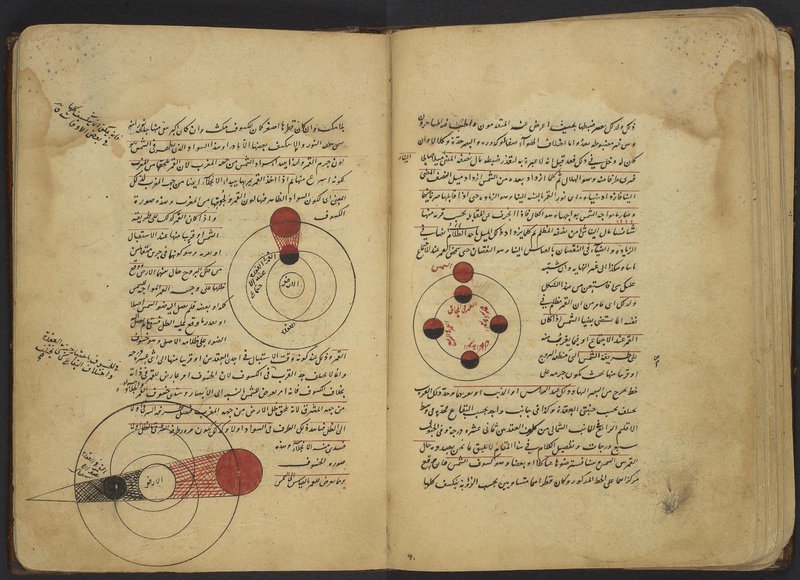

Qāḍī Zāda al-Rūmī (aka Salah al-Din Musa Pasha, 1364-1436), Sharḥ al-mulakhkhaṣ fī al-hayʼah (Commentary on Maḥmūd ibn Muḥammad ibn Umar al-Jighmīnī's Mulakhkhaṣ fī al-hayʼah [Epitome of Astronomy]). Samarqand, end of Ramadan 830 AH (25 July 1427). LJS 408, paper, in Arabic with some Persian. Fols. 42v-43r.

Little is known about the author of the Mulakhkhaṣ fī al-hayʼah except that he was a Persian physician by the name of Maḥmūd ibn Muḥammad al-Jighmīnī (d. c. 1221), and that he also wrote an epitome on Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine. His astronomical text became very popular in the Arabic-speaking world during the late fourteenth century, and its methods of calculating longitude inspired numerous commentaries, many of which were widely distributed in their own right. One such commentary was that of Qāḍī Zāda al-Rūmī, a Turkish mathematician and astronomer at the Samarqand Observatory established by Ulugh Beg, the Timurid governor of Transoxiana to whom this text is dedicated. This manuscript, which contains twenty-three astronomical diagrams, was produced during al-Rūmī’s lifetime; indeed, the copyist claims in a marginal note to have heard one part directly from the author (fol. 59).

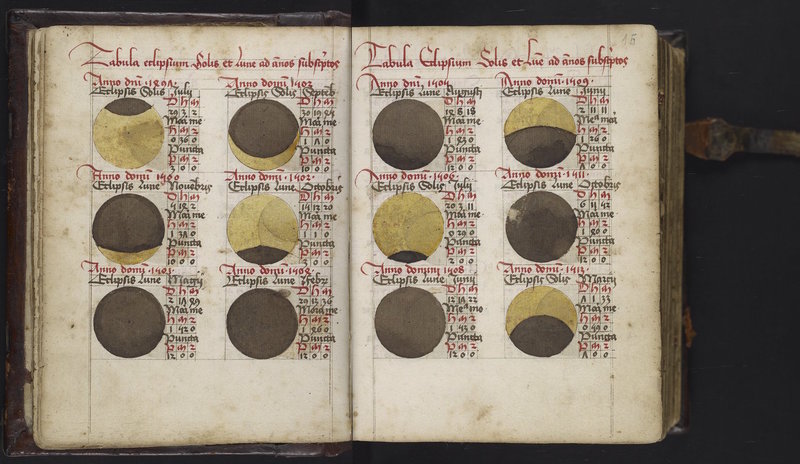

Johannes Regiomontanus (aka Johannes Müller von Königsberg, 1436-1476), Calendarium and Ephemerides. Austria (Lambach?), 1500. LJS 300, paper and parchment, in Latin. Fols. 14v-15r.

A major figure in fifteenth-century German astronomy, Regiomontanus achieved such wide renown that he appears in Schedel’s 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle holding an astrolabe. He was a friend and collaborator of Georg von Peuerbach, completing Peuerbach’s abridgment of the Almagest in addition to publishing his own works on arithmetic, trigonometry, and astronomy. This lavish manuscript was produced after the first edition of the Calendarium and Ephemerides in 1476, and may reflect a patron’s desire for a more deluxe object. The Calendarium includes information on lunar and solar eclipses, variations in day length, and the zodiac and planets for 1475-1530. The Ephemerides provides positions for the sun, moon, and planets for each day of the year from 1480 to 1506, with a pink finding tab at the beginning of each year. A liturgical calendar at the beginning of the manuscript includes customized additions to the printed text that suggest a patron monastery in southern Germany or Austria, most likely the Benedictine abbey in Lambach due to the inclusion of its patron saint, Kilian (feast and translation, 7 and 14 July). On display are some of this manuscript’s eclipse diagrams, which appear at the beginning of the Calendarium (fols. 12r-16v) and on the first page of most years in the Ephemerides.

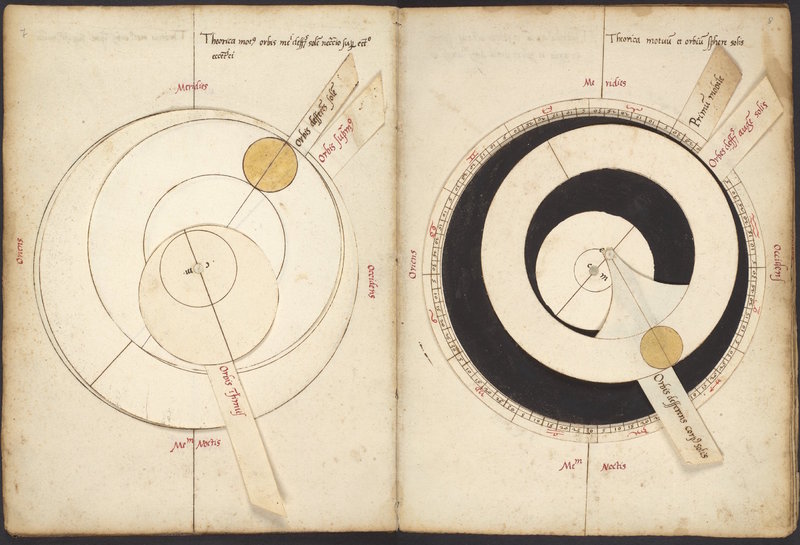

Illustrations to the Theoricae novae planetarum by Georg von Peuerbach (1423-1461). Italy, mid-16th century. LJS 64, paper, in Latin. Fols. 4v-5r.

Created to accompany Georg von Peuerbach’s Theoricae novae planetarum (1454), this codex attests to the enduring relevance of Ptolemaic astronomy in the early Renaissance. The volvelles (rotating discs) on these pages represent the solid “orbs” associated with the sun; like Ptolemy, Peuerbach believed that celestial bodies orbited within spherical shells. Page 7 shows the deferent orb of the sun between the two deferent orbs of the sun’s apogee (the point in its orbit at which it is furthest from the Earth). Page 8 combines the two deferent orbs on the middle disc, showing that they are concentric with the outermost sphere of the world (Primum Mobile). These delicate constructions of paper and thread are rarely as well preserved as in this manuscript.

Peuerbach’s text is essentially an updated version of the anonymous thirteenth-century Theorica planetarum, a popular university text often bound with Sacrobosco’s Tractatus de sphaera (as in MS. Codex 1881). The Theoricae novae planetarum, which incorporates information from the Alfonsine Tables, was first printed in 1472 under the supervision of Peuerbach’s student Regiomontanus; nearly sixty editions followed during the next two hundred years. Supplementary volvelle manuscripts such as this one may have been inspired by Peuerbach’s Speculum planetarum, a short text on astronomical volvelles.